A Simpler Guide to Ethereum

If you’re new to crypto and feeling overwhelmed - welcome, you’re in the right place.

Some of my smartest friends have started spending more time learning about Ethereum, and through that process, several of them have asked me similar questions, usually about specific definitions (like “what’s gas?”) or broad conceptual pieces (like “how does Uniswap work?”). These questions inspired me to put together A Simpler Guide to Ethereum.

How to Use this Guide

This guide is broken up into five main sections:

- An entry-level “Ethereum 101” section,

- a deeper look at some more complicated concepts in “Ethereum 201”,

- a section about identity in the context of crypto,

- a decentralized finance section, and finally,

- a section on the future of Ethereum, specifically in terms of the transition to Proof-of-Stake (don’t worry if this doesn’t mean anything to you yet!).

In each section, I define various complicated terms and compile useful diagrams to explain some of Ethereum’s most important conceptual topics in plain English. I’ve also included additional resources for continued learning at the end of the guide.

You can use the different sections of this guide as a quick reference check when learning about Ethereum, or as a point of inspiration for further exploration, or as a link to send your friends that are newly interested in crypto. For example, you could CTRL+F “Uniswap” to learn more about decentralized exchanges, or you could search for “wallets” to learn a bit more about non-custodial wallet security.

In one of his famous blog posts, Vitalik Buterin (one of the co-founders of Ethereum) wrote: “sometimes incredibly un-nuanced gross oversimplifications are something we need to understand the world.” I hope that, by boiling down these complex topics to their atomic parts, this guide can be helpful to anyone learning about the world of Ethereum.

Ethereum 101 - the basics

Before we can understand Ethereum, we need to understand the basics. In this section, I’ll explain what a blockchain is, how blocks get added to the blockchain, how Ethereum works as a world computer, and how smart contracts work.

Blockchain - A blockchain is a public record of all of the transactions that a certain network of independent computers processes and maintains. Rather than manage this transaction database centrally (in the way that Amazon or Facebook hold their data), there is no single owner of the data, making it decentralized. The computers in the network follow a specified set of rules and mechanisms to help them maintain the record of all of these transactions.

These rules help the computers agree (or “reach consensus”) on all of the different actions that have happened on the network: Did Computer A send money to Computer B, and did Computer B send those funds to Computer C, and when was that? What happened last week? What happened six months ago?

Computers in the network are independent, so Computers D and E (and F and G…..) might not know Computers A or B or C. The blockchain’s set of rules means that the individual computers can reach an agreement on what has happened in the history of the blockchain without needing to independently verify the accuracy of the data being provided by the other computers. In other words, the computers can agree without needing to trust each other! This trustless consensus between the computers in the network is pivotally important.

There are a ton of different blockchains, and each follows its own set of rules to reach consensus. The Ethereum blockchain specifically serves as the infrastructure and design space for all kinds of cool, new applications in sectors like gaming, art, finance, and social media.

Consensus Mechanisms - When all of the individual computers in the blockchain agree with each other about what has happened in the network, this is referred to as “consensus.” The individual computers follow the blockchain’s set of rules to reach consensus, and the computers go through the whole process of reaching consensus every time transactions are added to the chain. Once the computers reach consensus, a ‘block’ of transactions gets added to the ‘chain’ and becomes part of the history of the network. The rough idea is that if the computers can agree every time something gets added to the blockchain, then they can agree on the entire history of the blockchain, since they’ve had to agree every step of the way.

Consensus is one of the concepts that underpins the entire world of blockchains. Being able to validate what has happened in the network without needing to trust the individual participants in the network is an incredibly difficult human problem to solve, and blockchains are the best way to solve this problem. There are many different sets of rules (or “consensus mechanisms”) that help the individual computers in a blockchain reach consensus, but I’ll focus on the two big ones:

Proof-of-Work (PoW) - In Proof-of-Work, computers compete to solve really complex math problems. The network provides economic rewards to the first computer to solve the problem, which provides an incentive for the human behind the computer to keep the computers up and running (in other words, to ensure the network keeps processing transactions).

The process of competing to solve computationally-intensive math problems is called “mining”, as you may have heard before, and essentially, the process verifies that incoming transactions are legitimate and can be safely added to the blockchain. This is the set of rules that the Bitcoin blockchain and the current version of the Ethereum blockchain use.

PoW has its issues, mainly 1) the strongest (and most expensive) computers will end up solving the problems faster, so the rich will get richer and 2) solving hard math problems on computers requires a lot of energy consumption, which has been one of the biggest critiques to blockchains overall.

Proof-of-Stake (PoS) - Rather than use heavy computation to reach consensus (like PoW), Proof-of-Stake uses the risk of punishment (and some economic incentives too) to incentivize participants.

In Proof-of-Stake, participants put up money (technically, they “stake” their money), and in exchange, the participants are entered into a process of random selection. The computer that gets randomly selected does the job of validating the next batch of incoming transactions. When that randomly-selected computer does the processing correctly (i.e, within the constraints of the Proof-of-Stake rules), the computer earns a reward.

If the participant that gets randomly selected by the network does something against the Proof-of-Stake rules, the money that that computer staked gets reduced (or “slashed”).

By randomly choosing computers to validate the transactions, PoS blockchains don’t ask all of the computers in the network to work on those difficult math problems at the same time. Skipping that heavy computation mitigates the two major problems of PoW. This is in part why Ethereum plans to use this set of rules to reach consensus when Ethereum’s next-generation blockchain is deployed, slated for later in 2022.

Nodes - For the Ethereum blockchain to work, participants in the network need to run a certain piece of software to help them interact with the Ethereum blockchain. I like to think of each node as an independent computer running “Ethereum software.” All else equal, having more nodes (participants in the network) is good for the concept of decentralization, but sometimes, maintaining nodes can be a bit of a hassle, so there are a few types of nodes with different purposes:

Full Nodes - Full nodes store full blockchain data and help verify the blocks that are getting added to the blockchain. Full nodes also provide proofs that show that past transactions are valid.

Light Nodes - Light nodes are a type of node with less functionalities than a full node, by design. Instead of storing full blockchain data, light nodes just store the much smaller ‘proofs’ of past transactions. These light nodes help more people participate in the network, since they store less stuff and are cheaper to run.

Archive Nodes - Archive nodes are the librarians / Wikipedia’s of the Ethereum world. They store everything that the full nodes keep, and more. Analytics tools and wallet providers might use an archive node to pull information from way back when.

Clients - This is the “Ethereum software” that helps computers (nodes) interact with Ethereum. Individual nodes can pick which type of client software they want to use, but having a few different types of clients is important for decentralization, in case one of these clients has some sort of bug or issue. There are two types of clients; execution clients and consensus clients, but that’s beyond the scope of this guide.

Today, there are a handful of Ethereum clients available, and the Ethereum community has recently been campaigning the largest node-running institutions to diversify the clients they run on their nodes. It’s important to note that anyone who wants to participate in Ethereum can build their own client, which means that users don’t have to trust a third-party entity to verify the blockchain for them.

State - The Ethereum blockchain’s state describes what the different account balances on the blockchain look like at any given point in time. Once something new happens to the blockchain (like a new block of transactions getting processed), then the state gets updated to accurately reflect what the blockchain looks like after those new transactions are included.

Ethereum’s state holds information about the different accounts and their account balances. In other words, once the blockchain validates new transactions, the state is updated to reflect the new account balances, using the information from the new transactions that were just added.

Sidebar - How do blocks get added to the blockchain?

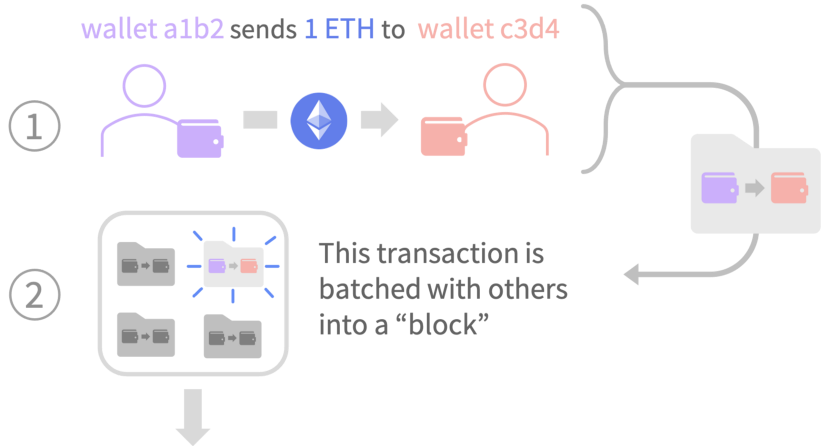

One user might want to send some money to another person using the Ethereum blockchain. Once the transaction is initiated from the side of the first user, the transaction needs to be added to the chain of transactions before the receiving user has the funds.

When a transaction like this is being added to the Ethereum blockchain, the entire process of reaching consensus amongst the nodes needs to occur before that transaction can be added to the blockchain and become a part of the history of that blockchain.

In the diagram below, the transaction in question is the simple one described above - just one user sending funds to another user. This transaction gets bundled into a block and waits for the nodes to work together to reach consensus and add blocks to the blockchain.

Image from: Understanding Ethereum

Smart contracts - Smart contracts are somewhat similar to digital versions of the traditional contracts that we are used to dealing with in the physical world. In a traditional contract (such as an employment contract or a lease for an apartment), two or more people make up a set of rules, then use lawyers and the legal system to enforce the rules in the contract.

In smart contracts, two or more people still set the rules, but instead of using the legal system for enforcement, the smart contract is written as programming code and posted to the blockchain (or “deployed” on the blockchain). Instead of having lawyers enforce the contract’s rules, the contract runs automatically based on what has been encoded into the code.

The sidebar above describes blocks getting added to the blockchain. Smart contracts are code that is deployed onto the blockchain via a transaction that gets included in a block. Smart contracts can then be ‘called’, or interacted with, by future transactions. A simple example would be if Person A and Person B wanted to bet on the price of Bitcoin in two years. Person A believes Bitcoin will be over $100k on 1/1/2032, while Person B believes Bitcoin will be below $100k on that date. Person A and Person B could set up a smart contract, place their funds into the smart contract, and set up a simple rule - if Bitcoin is above $100k on 1/1/2032, the smart contract releases funds to Person A, and if not, the smart contract releases funds to Person B. Simple, straightforward, and trustless.

Smart contracts allow anyone to trustlessly deploy code to a global computer, and they allow anyone to trustlessly verify what the code says (as long as they can read the code!). As a result, the existence of smart contract technology has opened up a massive opportunity for an emergent wave of decentralized applications that wouldn’t be possible without blockchains.

The biggest difference between Bitcoin and Ethereum is that Ethereum kicked off a wave of smart contract computing platforms, which are blockchains that enable smart contract code to be written and deployed directly on that blockchain. Josh Stark at the Ethereum Foundation wrote a piece about smart contracts that I recommend if you’d like to dig deeper into this concept.

Ether (ETH) - Ether is the native currency that powers the Ethereum blockchain. In Proof-of-Work, the rewards that go to the computers that solve the hard math problems are paid in ETH, and the capital that participants stake in Proof-of-Stake is denominated in ETH (technically, 32 ETH).

Ether is the name of the cryptocurrency, Ethereum is the name of the network.

the Ethereum Virtual Machine (EVM) - the Ethereum Virtual Machine is the name for the ‘imaginary’ computer that’s made up of all the individual small computers that participate in the Ethereum network. This single big computer isn’t an actual ‘physical’ computer in the sense of being in one single location, but it works exactly how a really big (like, planet-wide) computer would work.

The state of the Ethereum blockchain lives on this computer, and the EVM also holds the rules for updating the state when the next block gets added to the blockchain. If someone on the Ethereum network wants to include smart contract code in one of their transactions, that code gets run on the EVM.

–

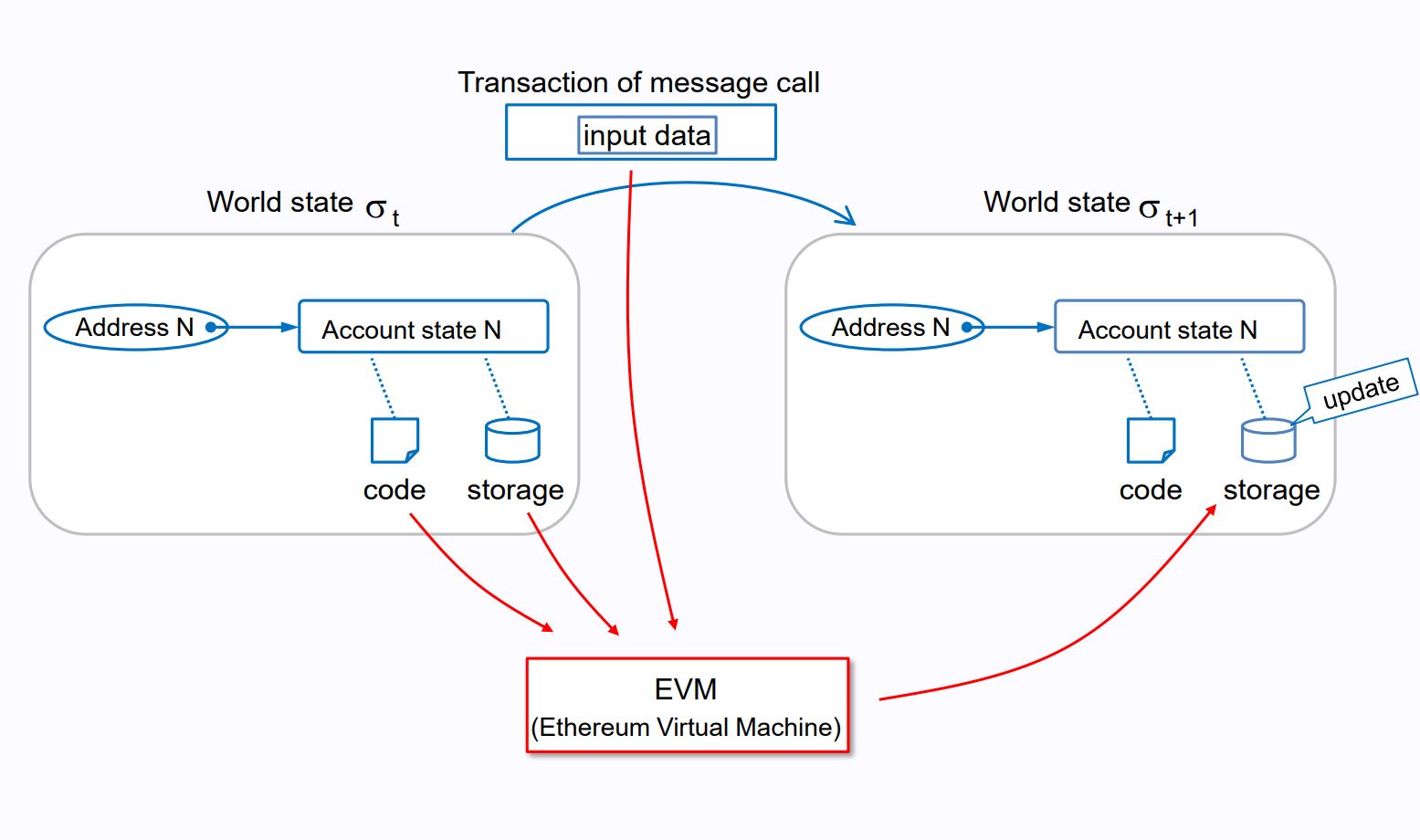

Sidebar - How does the EVM work?

While it’s probably unnecessary for a beginner to understand the intricacies about how the EVM works, the EVM is an important component of the Ethereum blockchain and gives you a sense for how decentralization operates at scale. The below diagram, while a little complex, paints a great picture. Let’s go step-by-step at what you’re looking at:

Before anything happens, we start with the state of the Ethereum blockchain at a given point in time. This is the box all the way to the left called “World state σ t.”

A transaction, like a transfer of ETH from one wallet to another, gets added to the Ethereum blockchain. This is the “Transaction of message call” box at the top of the diagram.

The state of Ethereum before the transaction (again, box on the left) plus the input data from the new transaction (box on the top), go to the EVM. Here, the EVM updates the new state.

Once the EVM updates the state, the new state (“World state σ t+1”) is stored.

Image from: Ethereum EVM Illustrated

Tokens - Tokens generally refer to some asset on a blockchain. Tokens can represent many different types of assets; for example, a token could be an asset that is supposed to act like a currency, or a token could be an asset that gives the holder the right to vote in a specific decision-making process (a ‘governance’ token), or a token could be something else entirely. Tokens are atomic units of value for different kinds of assets within the world of crypto.

Fungible Tokens - The term ‘fungible’ refers to some set of mutually interchangeable goods or objects.. This is not a crypto-native term; currency is typically referred to as fungible. For example, the $1 dollar bill in my pocket can be exchanged for the $1 dollar bill inside of your pocket, and both of those could be used to buy $1 of something. They’re worth the same. When applied to crypto concepts, fungibility refers to whether or not a crypto asset is interchangeable with another in its’ set. My ETH is fungible with your ETH.

Non-Fungible Tokens (NFTs) - Non-Fungible Tokens refer to any digital assets that are unique and are therefore not interchangeable.

While popularized through digital art and collectibles, NFTs can be any unique digital asset. It just so happens that digital art and collectibles are one of the first use cases for NFTs that have resonated with the broader public. NFTs have helped get a ton of people interested in crypto, but I think the rise of NFT projects like Bored Apes and NBATopShot have led the broader public to underestimate the other types of utility that are enabled by having unique digital assets on a trusted settlement layer like the Ethereum blockchain.

Conceptually, NFTs can also be used for a variety of other use cases outside of just digital collectibles. If a product or service needs to be able to verify the ownership and provable scarcity of a certain digital asset, NFTs on a public blockchain can help. For example, concert venues might use NFTs to represent tickets for a concert, or video game designers could turn hard-to-get in-game assets into NFTs so that users can transfer and trade them amongst themselves.

One twist to this concept - some assets can be both fungible and non-fungible, depending on the set that they’re being compared to. For example, if I have an antique $1 US Dollar bill from the 1800s that I keep in a glass case as a collectible. It’s clearly a different dollar bill (non-fungible!) than the dollar bill I have crumpled up at the bottom of a pocket in my pants.

Still, if I took that dollar bill out of the glass case and tried to spend it at Starbucks, they’d (probably?) accept it, because in some ways, it’s fungible with the other dollar bills, even though in other ways, it’s clearly different.

Ethereum 201 - deeper down the rabbit hole

In this section, I’ll explain why gas costs are so high, how composability works, and how users interact with applications built on Ethereum.

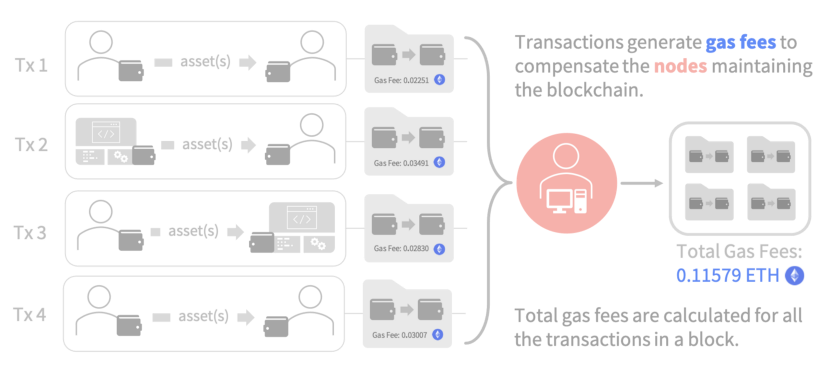

Gas - Every interaction with the Ethereum blockchain has a cost to it (gas), and that cost depends on how much computation it takes for the EVM to run that specific piece of code. Because each block in the blockchain only has room for a fixed number of transactions, the concept of ‘gas’ helps Ethereum allocate the scarce resource of ‘blockspace.’

More complex transactions may require more gas to complete. For example, sending ETH from one wallet to another might just require a few lines of code in the EVM, so it will require less gas than a more computationally-intensive interaction, like swapping several coins on a Decentralized Exchange (more on this below in the Decentralized Finance section!).

You might think of gas as similar to a fee that a centralized credit card company takes to operate its services. Visa, for example, takes a flat 3% of all transactions happening via the Visa network, which they’ve built, operated, and maintained since the 1950s. By contrast, Ethereum’s “fee” (gas) is variable, based on the supply and demand for the network at the time of the transaction. Gas fees are paid out to computers that participate in the Ethereum blockchain (more on this below).

Gas is denominated in ETH, and users can decide to pay more in gas (by ‘tipping’ the computers processing transactions) to speed up their transaction time, increasing the chances of their transaction getting included in the next block.

Gwei - Gas prices are technically denoted in wei, which is just a very small increment of ETH. 1 wei is equal to 0.000000000000000001 ETH (1 quintillion weis, so 5 commas = 1 ETH). 1 gwei is equal to 1,000,000,000 wei, so gwei to ETH just makes the increments easier when comparing gas prices.

Users have gotten used to quoting gas prices in gwei. Something like 0.0001 ETH would be 1 gwei, which is a very low gas fee. Users can use Gas.Watch to keep an eye on current gas prices. Gas fluctuates based on the demand that exists for getting included into the blockchain.

I think it’s pronounced gwey, but I’ve heard people say goo-ee.

Sidebar - Why do we need gas, and how does it work?

The computers that validate transactions for the blockchain need to be economically incentivized. If they weren’t economically incentivized, it would be very difficult to convince people to run and maintain these computers and keep the blockchain running, and if there aren’t enough computers running, blockchains become too centralized in the hands of just a couple of controlling users.

As mentioned above, participants are paid in gas based on the demand that exists for getting included into the blockchain.

Image from: Understanding Ethereum

Solidity - Solidity is the name of the programming language that people can use to write smart contracts and build decentralized applications on the Ethereum blockchain. Crucially, Solidity is a Turing-complete programming language, which basically means that “anything you could conceivably write into code can be written using Solidity.” This means that developers can use Solidity to do a ton of different types of cool stuff on Ethereum.

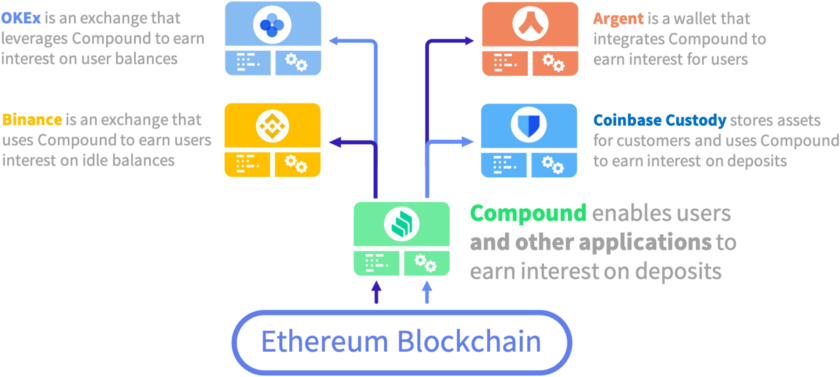

Composability - Because smart contracts are deployed as open-source code on the Ethereum blockchain, anyone can build on top of these smart contracts (or ‘fork’ the code and change it up yourself), which means that applications on Ethereum (and other similar blockchains) are composable.

You can think of composability like an API on the blockchain. While developers have arguably been able to build software on top of other pieces of technical infrastructure in earlier generations, the main difference with crypto composability is that all of the underlying protocols are decentralized. In other words, developers don’t have to worry about a centralized entity owning all of the underlying data, suddenly changing its rules, or restricting access to developers, like what happened to developers building on Twitter APIs in 2018.

Sidebar - What are some examples of composability? How does composability actually work in practice?

The concept of composability is the idea that developers can build an application using other applications that have already been built and deployed onto a public blockchain.

For example, Compound is a DeFi application that lets users earn interest on deposits, like a high-powered savings account. If a developer at a project like Argent (a crypto wallet) wants to embed Compound into the application they’re building, the developer can integrate Compound easily without having to reinvent the wheel. That’s composability.

Image from: Understanding Ethereum

Ethereum Improvement Proposal (EIP) - Because a blockchain like Ethereum is inherently public, decentralized, and open source, the way that the developer community around Ethereum makes changes to the protocol is a lot different than how decisions are made in a centralized entity. Modern open source communities (like the vibrant community around Linux or Python) are far more analogous to the Ethereum development process.

The Ethereum community has developed processes that outline how members of the community could propose an improvement to the Ethereum protocol. These processes provide a public forum for discussion and encourage open-source participation from the community, which is important since Ethereum is a decentralized blockchain and relies on a globally-distributed community to monitor and improve the blockchain.

These proposals can be about the core rules that the blockchain follows (for example, when reaching consensus), or the proposals can just be proposing standardized versions of a core building block of Ethereum, like non-fungible tokens or wallets (described later on in the guide). Standard versions of these types of things make it easier to know that the code will work as intended when someone takes advantage of the composability of Ethereum to build an application using these standardized pieces.

Ethereum Request for Comment (ERC) - ERCs are a type of EIPs. Specifically, ERCs are EIPs that describe “application-level standards and conventions.” This specific category of EIPs merits a mention in this guide because ERCs are the contract standards that act as a template for some of the most important and well-known use cases within Ethereum. Developers can use these contract standards when building on Ethereum to save some time and effort, instead of having to start from scratch. Some of the most well-known ERCs are:

ERC-20 - This is a token standard for fungible tokens.

ERC-721 - This is a token standard for non-fungible tokens.

ERC-1155 - This is a token standard that optimizes some parts of the ERC-20 and the ERC-721 standards, and is commonly seen in the fractionalization of non-fungible tokens.

Testnets - Testnets are copies of blockchains that allow developers to play around and test how their code will work on the ‘mainnet’ blockchain. When developers deploy smart contracts on a blockchain, that code will be viewable for as long as that blockchain is active, even if that specific smart contract isn’t being used anymore. That permanence, plus the possibility of the smart contract interacting with huge sums of money, means that developers want to be sure that their code operates the way they intend it to.

In Ethereum’s case, there’s a bunch of testnets (like Rinkeby, Ropsten, and Kovan) that developers can test their code on without actually risking user funds. Testnets are practice development environments for software developers in crypto.

Faucets - Faucets distribute ‘fake’ ETH to developers so they can use that fake ETH to test smart contracts on the testnet. The developers will need this ETH to deploy the contract and interact with it, but the testnet ETH doesn’t have real economic value like ETH on mainnet does. Faucets are easy ways for developers to get some fake ETH on testnets.

Imagine you’re a developer ready to deploy a smart contract on Ethereum. Let’s pretend the smart contract you’re working on will handle some funds, maybe something like a decentralized exchange (discussed in the Decentralized Finance section below). First, you want to test that smart contract on a testnet to make sure the code is working as planned. You’re going to want some ETH on the testnet to play with your smart contracts.

But, remember, the testnets are copies of the Ethereum blockchain, so the ETH on a testnet is essentially ‘fake’ ETH, in the sense that it isn’t exchangeable with ETH on the main Ethereum chain. You still want to test your contract using ETH, to see how it might work in practice, so faucets make it easy to get some fake ETH to play around with on the testnet.

Oracles - Oracles are used to connect blockchains to external systems, as needed. At some point, some of the applications that can be built on Ethereum will want to interact with a data feed that isn’t secured by the Ethereum network. Some data, like today’s weather or the score of a basketball game, has to come from “off-chain”, so oracles are the connection to the “real world.”

Oracles can be used to check the weather near orange crops in Florida for the sake of crop insurance, or an oracle can be used to verify scores for a decentralized sports betting application. Oracles present a potential trust issue (since the network of computers that make up a blockchain can’t practically prove what the weather was like in Florida), but there are pretty good solutions out there for applications that need an oracle.

Providers of Oracles (like Chainlink) come up with systems to try and ensure that their oracles are not a vulnerability, but an oracle can always be a point of weakness for a blockchain. You could imagine setting up a type of consensus mechanism for oracles where, even though there’s a trust vulnerability (since the data comes from off-chain so it can always be manipulated in some way), it still requires 9 of 16 oracles to agree on what the oracle network is saying (or some similar mechanism).

Mempool - When a transaction has been submitted by users but hasn’t been validated and added to the blockchain, the pending transaction gets added to a waiting area called the mempool.

Before a transaction can be processed, the computers in the network will have to check whether the transaction is valid. For example, the transaction might spend more money than available in the account that’s sending the transaction, or the private key might not match with the public key of the wallet sending the transaction (more on this below in the Wallets and Identity section). While the computers in the network check these types of potential issues, the pending transactions wait in the mempool.

Technically, each individual participant in the network has its own mempool, but for the sake of this guide, it’s fine to imagine the mempool as a single waiting area for all of the blockchain’s transactions. Usually, transactions wait in the mempool for anywhere from a few seconds to a few minutes, but this will depend on demand (more on scalability below!).

Pending transactions on Ethereum can be viewed on a data provider like Etherscan.

Sidebar - What are some examples of composability? How does composability actually work in practice?

Users will almost certainly just be using a web application through a browser like Chrome. Those web applications are built using specific packages of libraries (like web3.js or ethers.js) that help web apps interact directly with the nodes of a blockchain.

Developers build applications that interact with Ethereum through nodes running client software - in the below example, the client is Geth, a command line interface used to interact with the Ethereum blockchain. There are also “Nodes-as-a-Service” providers like Infura that let developers easily interact with nodes managed by a service provider, similar to how developers can tap into AWS to access server space. Those nodes then interact with the smart contracts and individual account balances on the Ethereum blockchain.

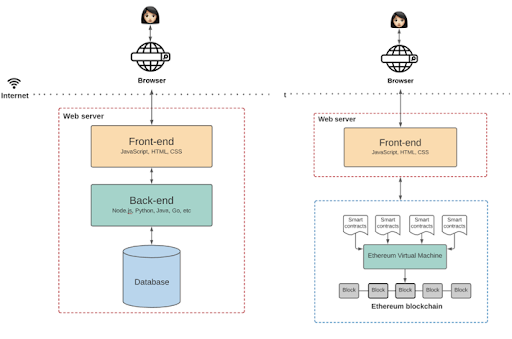

This isn’t very different from the “back-end” vs. “front-end” of other software products today. On the left of the diagram below, we can see how a user might connect to a traditional web application.

And right next to that image is an example of what the architecture of an Ethereum-based application might look like. Similar! What’s the difference? Ethereum serves as the back-end infrastructure for the crypto application, which makes it global, permissionless, and uncensorable.

Image from: The Architecture of a Web3.0 Application

Wallets and Identity

By design, blockchains enable users to self-custody assets, but wallets are more than just self-custody - wallets are also how users represent themselves in the world of crypto. In this section, I’ll explain what DAOs have to do with identity and how users can be smart about wallet security.

Wallets - A crypto wallet holds your assets, just like how your physical wallet holds your cash. But these wallets also hold information that represents you and your actions, like the applications you’ve interacted with and the trades you’ve made using that wallet.

Remember that, by design, transactions on blockchains are public, so when you use your wallet to do something on Ethereum, your wallet holds traceable, public data about the transactions managed with that wallet. This traceable data underpins the idea of ‘owning your own data’ in web3 - your assets, your transaction history, your interactions with decentralized applications travels with your wallet. Also, unlike physical wallets, many crypto users have a few different crypto wallets for different purposes.

There’s a few additional definitions needed here to fully explain wallets:

Public Key - This is a long code word that represents the outward-facing address of a wallet. Public keys are like your home address; the home address is unique, the address isn’t secret (public records, etc.), and the address corresponds specifically to one home (or in this case, one account, which is yours)..

You might share your address with a friend who wants to send you a letter or a gift, but if a random person saw your home address in the local government property records, it wouldn’t be a big deal. It’s fine if someone sees your public key.

Private Key - On the other hand, the private key is the password for actually doing anything with your wallet, so it is NOT okay for others to know your private key. The private key corresponds to a specific wallet’s public key, so if someone knows the private key, they have full access to that wallet!

Private keys are like the actual key to the home - you wouldn’t mind if someone randomly knew your address, but if you knew they had the keys to the house, you’d be rightfully worried. It’s worth reiterating - anyone with access to the private key can access that wallet. Do not share your private key with anyone, and don’t keep your private key stored anywhere where someone else might find it.

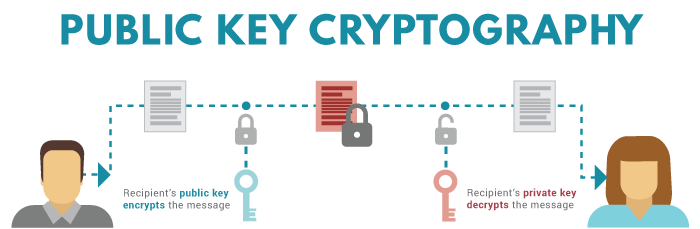

Sidebar - How do public keys and private keys work?

The mechanism behind public and private keys is a really important fundamental topic to understand. Basically, public keys and private keys are used in a method of encrypting and verifying authenticity called private key cryptography.

Remember that public keys are outwards facing. When a user sends a transaction to their friend’s wallet (by using their friend’s public key), the user is putting a padlock on the transaction that can only be unlocked when their friend confirms that they have the specific private key of the wallet that the transaction was sent to. Despite the transaction being visible (because it’s on a public blockchain), it can’t be ‘unlocked’ without the specific private key corresponding to the wallet that now holds the funds.

Whether you are a developer building a project on Ethereum or just a user, it’s important to understand the distinction between public and private keys. Misusing (or misplacing) public and private keys may have massive financial consequences for users, and unlike forgetting a password for a centralized website, there is no way for application developers to help recover it. As more people create crypto wallets and transact on the blockchain, this mode of transacting will become more normalized. But in the meantime, it’s important to be aware of the learning curve and help explain it to others.

Image from: How to Generate Public and Private Keys

Seed Phrase - These are sets of random words (usually 12-24 words) that act as a final wallet recovery tool in case of emergency. Seed phrases should be treated with the same level of security as private keys, since losing your seed phrase or storing it where someone else will find it means that everything in the wallet is exposed. It’s important that all users exercise the appropriate steps to keep their seed phrases safe and confidential.

Wallet application developers don’t have access to the seed phrase, so if you lose your private key and seed phrase, your wallet cannot be recovered. But if you lose your private key, you can recover your wallet with the seed phrase.

Custodial Wallet - These are wallets managed by a custodian (any centralized entity that is responsible for holding the currency within those wallets) such as a regular Coinbase account. These custodians take on the responsibility of managing the underlying assets in that wallet (so users won’t have to manage their own private keys if they use a custodial wallet) in exchange for providing users with a more centralized, streamlined user experience.

This user experience doesn’t usually include crypto-native authentication mechanisms - for instance, a user can use a Google email address and password to log into their Coinbase account.

Custodial wallets are a great way to get started in crypto and a useful route for transferring funds from cash into crypto. On the flip side, because these custodians are centrally owned and managed, they carry some of the problems that decentralization set out to solve - like data ownership, control of the flow of information, and potential regulatory requirements.

There’s a popular saying in crypto about custodial wallets - “not your keys, not your coins.” Even Coinbase CEO Brian Armstrong has spoken about the importance of non-custodial wallets because of the risk of government regulation of custodial wallet providers. For users who prefer to manage their assets and transactions in a fully decentralized way, non-custodial wallets are a better fit.

Non-Custodial Wallet - These are wallets managed by… you! Software providers (like MetaMask, Argent, or Rainbow) provide software for users to access their wallet, but crucially, the wallet’s assets live on the blockchain, not in the software of any of the wallet providers. So if something were to happen where MetaMask became inaccessible, users could easily jump onto Rainbow, import their wallet (without the need for MetaMask’s approval) and interact with their assets through Rainbow. There’s also non-custodial hardware wallets, where the private keys are stored directly on a physical device (usually a little piece of metal that looks like a USB).

Non-custodial wallets come with the burden of managing public/private keys and seed phrases, but they also give users self-sovereignty (owning the assets directly) and a single identity into the world of Ethereum. Ethereum applications allow for users to “Sign in with Ethereum,” which really means “sign in using your non-custodial wallet.” Because of this, non-custodial wallets are a representation of a user’s identity, and these wallets open up a ton of design space in crypto like new ways to think about identity, credentialism, and ownership.

Social Recovery Wallets - This is a type of wallet recovery tactic enabled by some of the non-custodial wallet providers. Instead of needing to store a seed phrase, which people have famously lost before, users can assign people in their social networks to verify that the wallet corresponds to the person that it is supposed to correspond to.

With social recovery wallets, users can use the trust of their social circles as the backstop for their non-custodial wallets, while still retaining the self-custody / decentralization / single-sign-on benefits of non-custodial wallets on blockchains. Argent is an example of a social recovery wallet.

Sidebar - How can users be smart about wallet security?

I’m not going to use a diagram for this sidebar, because it’d be impossible to fit all of the necessary information about wallet security into a single diagram. Wallet security is incredibly important, and it is worth the effort to spend a small amount of time digging deep on best practices for managing your own funds in the world of crypto.

Thankfully, Punk6529 published an incredible tweet thread on the subject that covers all of the information needed to be smart about wallet security. Vitalik has also written a great article on the importance of social recovery wallets. And here is more information from hardware wallet provider Ledger on wallet security.

Here are some highlights from Punk6529’s thread, although I strongly recommend going through the thread yourself:

“Unlike your public key, you must never ever show your private key to anyone. If someone has your private key, it is GAME OVER.”

“Address/Public Key: Your email address (can be shared)

Private key: The password to your inbox (never share)

Wallet: Holds private keys

Seed phrase: Recovery system for private keys (never share)

Passphrase: Optional: extra password to create new wallets (never lose)”

“Security/resiliency are opposite goals. Printing flyers with your private keys is very resilient but your NFTs will be gone.

You can easily solve security by destroying your private keys. But then you can’t access your NFTs either.

The art is balancing these two goals.”

Ethereum Name Service (ENS) - The Ethereum Name Service is an open naming system for the Ethereum blockchain, somewhat similar to a domain name provider for traditional websites. ENS maps addresses in Ethereum to a human-readable name, so I can use something like “brunny.eth” as my address rather than the longer form of my public key, which is 0xF67cAEbBbE7b630d137d2901637C02899ED3211b.

You can try it from your crypto wallets directly (custodial or non-custodial) - set up a small transaction to send a few cents of ETH, but write “brunny.eth” as the recipient, instead of my specific public key. The service should match “brunny.eth” with the wallet address.

ENS is basically a public good, and ENS names are so important to identity in the Ethereum ecosystem that they deserve their own explanation.

Decentralized Autonomous Organizations (DAOs) - DAOs are the crypto-native way to organize. DAOs can be companies, or non-profits, or social groups, or really any type of organization that uses crypto-native principles to organize themselves. By crypto-native principles, I mean concepts like community ownership, transparency, and decentralization, although it’s important to note that decentralization is a spectrum and not a binary off/on switch.

Unlike traditional corporations, which are centrally owned and managed in their entity creation and leadership team structure, DAOs design structures for operating crypto-native projects and businesses without centralized entities making decisions. Instead, DAOs strive for community ownership of projects. Another objective for many DAOs is full decentralization and democratization. In other words, decisions are made by democratic votes of key participants in the DAO. DAOs can be used to vote on application-level changes to products built on blockchains, and DAOs can also be used to reward and incentivize participants in the system.

A few DAOs are actually pretty close to autonomous, in the sense that automated smart contract code runs many of the functions of the DAO. An example of this is DAOs in DeFi, where the core value proposition of the DAO is decentralized maintenance of some smart contract that’s serving some purpose in DeFi. Most DAOs are working towards progressive decentralization, and most are more similar to a group chat with a bank account than a truly autonomous organization.

DAOs are a social by-product of permissionless blockchains, non-custodial wallets, identity tools like ENS, and shared purpose of participants in the ecosystem. DAOs could deserve their own section (or entire guide!) but my personal opinion is that the DAOs we participate in crypto are a key piece of how we redefine our digitally-native identities, so the concept makes the most sense in this section.

Decentralized Finance

DeFi is arguably the most successful use case for Ethereum so far, with over $100 billion in assets locked into DeFi protocols on Ethereum. DeFi also tends to use the most confusing terminology. In this section, I define DeFi broadly, dig into some of the confusing terms used in DeFi, and explain how Uniswap, a decentralized exchange built on Ethereum, works.

Decentralized Finance (DeFi) - Decentralized Finance refers to any financial application, exchange, or system that operates entirely on a blockchain without centralized gatekeepers. Today, there are hundreds (if not thousands) of DeFi projects across a variety of blockchains, with applications ranging from decentralized exchanges to lending to options and futures contracts. The primary objective of DeFi applications is to reimagine the functions of centralized banking institutions in a world where no centralized bank holds the power.

As one example of how this might play out, consider the purchase of a share of stock on the stock market today. When Sally buys a share of Tesla stock through her brokerage (Robinhood, Charles Schwab, Vanguard, etc.), that share of Tesla bounces around through a handful of different intermediaries before it can get to Sally. Usually, the system works fine, and the act of bouncing through different intermediaries doesn’t get noticed by the general public. But sometimes, crazy things happen - like the 2008 Global Financial Crisis or the Gamestop mania of 2021 - and the system breaks (like negative oil prices and canceled trades).

When the system breaks, people want to find out who is responsible for the chaos. And when they start digging, they find out that the traditional financial markets aren’t as clear and transparent as they might expect!

Decentralized Exchanges (DEXs) - The first major DeFi building block. Blockchains have enabled a new type of exchange, where assets can be traded directly with a smart contract instead of with a layer of opaque middlemen and quasi-governmental institutions.

In the Sally Tesla stock example, instead of trading through a brokerage (like Charles Schwab), which routes trades through a marketmaker (like Citadel), both of which are subject to constraints imposed by United States clearinghouses (like the DTCC) - Sally just trades with Uniswap smart contracts! All of this code is transparent and public, so Sally can see the funds flow, with no opaque middlemen clouding her view.

These decentralized exchanges use blockchains and economic incentives to create a market for virtually any two assets (i.e, BTC and ETH, or US Dollars and Euros, etc.). I’ll explain how Uniswap, the biggest DEX by market share, works below.

To understand how these decentralized exchanges work, we need to define a few additional terms:

Liquidity Providers (LPs) - The opaque middlemen described in Sally’s transaction above do provide a useful function in our traditional financial system - they provide liquidity to the system. Whenever Sally wants to sell her stocks in the traditional financial system, she almost always can (during regular trading hours, at least…), because these middlemen are paid to provide liquidity to Sally and other market participants.

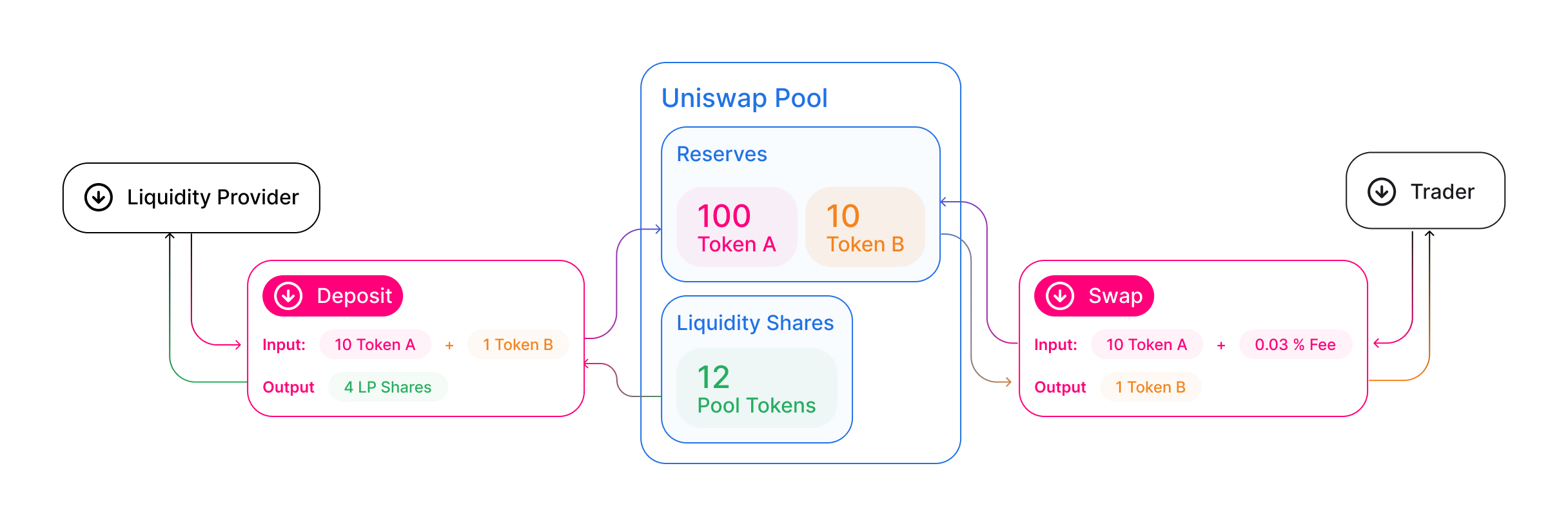

How does the smart contract in a decentralized exchange protocol have assets to trade? Liquidity providers. DEXs give individuals the opportunity to provide liquidity in return for a small percent of the trading fees that are generated when someone trades assets with the smart contract.

The most well-known model for LPs is Uniswap’s model, where LPs deposit the same amount in value of a pair of two tokens into a smart contract. Again, LPs deposit into these contracts in exchange for a percentage of trading fees. The LPs can withdraw the tokens they put in as liquidity whenever they want, but then they obviously won’t participate in the upside of future trading fees.

Automated Market Makers (AMMs) - This is a type of DEX. An automated market maker is a smart contract that uses an algorithm to set prices. Uniswap’s constant-product formula (x*y=k) is the most famous example here, but that’s beyond the scope of this guide. AMMs are just a formula or mechanism for setting prices without needing a human to set the prices instead.

Stablecoins - Stablecoins are digital representations of physical currency - they’re supposed to represent the value of the currency they’re pegged to, but as a digital currency living on a blockchain.

DeFi lets users do a lot with crypto assets, but it can be hard for users and investors to manage their assets in a fixed price range, because of the moving prices of crypto assets. Stablecoins serve as a way to keep less-volatile capital on a permissionless, decentralized blockchain, and they also act as reference prices to compare crypto assets.

Usually, stablecoins are pegged to the US dollar, but there are other currency stablecoins as well. There are both centralized and decentralized stablecoins, each with their own mechanisms for maintaining the 1:1 peg with the currency they’re tracking. And yes, crypto is disrupting the global financial system, but the major global currencies (US Dollars, Euros, Yens, etc) are still useful reference prices.

Total Value Locked (TVL) - TVL just means the total value locked in smart contracts on a given platform. TVL can be used outside of the context of DEX’s, since other applications besides exchanges might involve a liquidity provider mechanism (like lending, for example). Uniswap has several billions in TVL, and Ethereum as a whole entered 2022 with over $100B in TVL across applications.

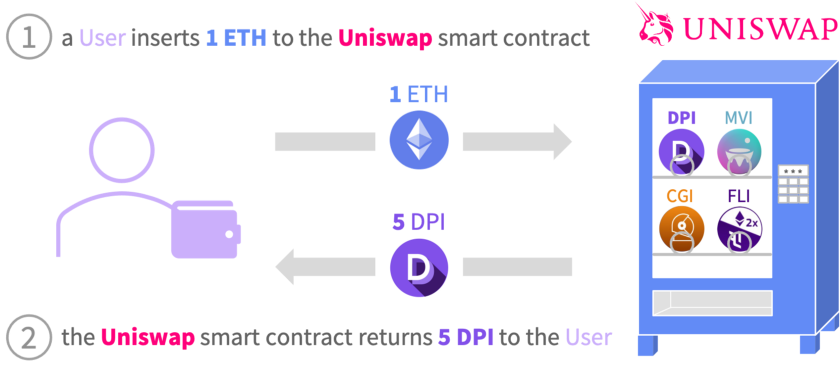

Sidebar - How does Uniswap work?

First, let’s talk through the user experience. When a user wants to use Uniswap (or another DEX) to swap a token, the user gets to use a simple frontend that Uniswap built around the more complex smart contracts behind the scenes. As the diagram below shows, the user can swap ETH (or any other token) for another asset, almost like a vending machine. Users can just go in and swap from any token into almost any other token. Simple!

Image from: Understanding Ethereum

But what’s actually happening behind the scenes? Let’s start with the blue box in the diagram below; this is the Uniswap smart contract where liquidity providers deposit their tokens (Token A and Token B in this case).

On the left of the blue box is the LPs relationship with this pool; the LP deposits in two assets, and in exchange, receives a pool token that corresponds to a claim on those two assets that they deposited. Those pool tokens can be redeemed at the smart contract for the assets that the LP put in originally, whenever the LP wants to redeem (here, traders need to be careful of the impermanence loss I describe below).

On the other end is the user in the above diagram. Without needing to have any interaction with the various LPs in the pool, the user can go in and swap one of the tokens in the pool for the other one. The user also pays a small fee that flows through equally to all of the liquidity providers in the pool.

Image from: Uniswap documentation

The following terms (and the whole DeFi rabbit hole beyond the introductory definitions) probably require their own deep dive. However, these can be some of the first terms and concepts that a new user into the world of Ethereum sees, so I believe they have an outsized influence on the amount of confusion for new entrants into the space, so they merit some extra work on my end.

Yield Farming - As the name suggests, yield farming is the practice of “harvesting” yields by moving your money around DeFi applications. These applications offer enticing rewards in exchange for using their applications. If you’ve ever had a friend tell you about the crazy 100,000% APYs they’re earning in DeFi, they’re talking about yield farming.

A lot of DeFi applications need lots of money on their platform (liquidity, like we described above) as a key function of the value proposition of that application, whatever it may be (exchanging assets, lending, etc.). These DeFi applications are left with two options; raise a billion dollars and provide that liquidity yourself OR offer crazy rewards for people to provide liquidity themselves, and have these yield farmers act as the liquidity on the platform instead.

But wait? Where do the crazy rewards come from?

Well, these applications are promoting these crazy rewards as some new innovative mechanism, but in reality, these rewards are usually just (expensive) customer acquisition costs. In other words, these applications have tokens that in some ways represent the value of the application, and they distribute rewards (the 100,000% APY) to get people to use the application (customer acquisition costs). These rewards can be a mix of native tokens and other types of tokens.

So yield farming is the practice of searching for these yields and moving capital to the applications that have the best chance of becoming lucrative. It’s almost a form of angel investing into DeFi applications.

Staking - This term gets thrown around a ton, but staking basically just refers to locking an asset for some period of time and getting some benefit from locking it up.

Usually, this term is used in decentralized finance, where users stake tokens in exchange for rewards, but staking could also apply to other stuff too. Many DeFi protocols use staking as a way to control the liquid supply of their protocol’s native token, similar to how a central bank tries to manage monetary supply. Investors are incentivized to lock up their tokens in the short term in exchange for economic rewards - sounds a lot like a bond to me!

Impermanence Loss - This term refers to the potential risk that Liquidity Providers have when providing liquidity in two or more tokens. In the Uniswap examples above, Liquidity Providers deposit two tokens to Uniswap in equal proportions and receive pool tokens that can be used to claim the two tokens back when LPs want to withdraw their capital.

One nuance here is that LPs deposit two tokens, each token having its own respective price (and price movements). When the LP wants to redeem the pool token in exchange for the two tokens, the price of the two tokens may have diverged significantly - one token price might be down 5%, and the other might be up 10%.

This divergence between token prices might mean that the LP would have been better off just holding the tokens individually instead of holding the pool tokens and earning the trading fees yield. Importantly, impermanence loss is labeled ‘impermanent’ because these are just ‘paper losses’ until the Liquidity Provider actually redeems the pool token - if the LP doesn’t redeem the tokens and just continues to provide liquidity until the prices converge, then the loss disappears.

A good primer on DEXs, LPs, and impermanence loss in different types of pools can be found here.

Layer 2 and Proof-of-Stake

2022 is colloquially known as the “Year of the L2” in Ethereum, and the much-anticipated transition to Proof-of-Stake consensus should happen sometime in the summer. This section will dig into the blockchain trilemma, the future of Ethereum, and how rollups work.

The Blockchain Trilemma - Every blockchain faces trade-offs between three concepts; decentralization, scalability, and security. The general consensus (as of early 2022) is that Ethereum gets a thumbs up for decentralization and security, but a thumbs down on scalability (gas fees! Ahhhhh!). Hopefully, a few scheduled improvements in the near-term will hopefully solve the blockchain trilemma for Ethereum. Below are explanations of the considerations associated with each of these areas - it’s important to understand how these trade-offs impact individual blockchains.

Decentralization - The Bitcoin whitepaper describes decentralization perfectly (my own emphasis added):

“What is needed is an electronic payment system based on cryptographic proof instead of trust, allowing any two willing parties to transact directly with each other without the need for a trusted third party.”

Blockchains act as an infrastructure layer that enables people across the world to interact with each other using only their computers, and without an intermediary.

Decentralization of blockchains is a spectrum; If the blockchain can be shut down by a small minority of users, or if the cost to participate in the network is too high (gas fees or the cost of setting up a computer to participate in the network), then the blockchain falls towards the centralized end of the spectrum. The greater the centralization, the greater the risk of monopolistic power and exploitation.

Security - Security refers to how difficult it would be for the underlying blockchain to get hacked or manipulated by outside parties. A good rule of thumb is the 51% majority; if someone is able to control 51% of the computers that are processing transactions for a specific blockchain, they can probably hack and compromise the security of the network.

There’s some deeper technical considerations here, but 51% helps paint a picture for the trade-off between security, decentralization, and scalability. More independent computers processing transactions for a given blockchain means more decentralization and more security (more computers = smaller chance of anyone getting 51% of the network). But more independent computers in the network means that each of the independent computers needs to communicate with an even bigger set of other computers in the network, which slows things down…

Scalability - …which leads us to scalability. Blockchains can get very congested when demand for them is high. For example, Ethereum has famously had periods of exorbitant gas fees, specifically when the network is getting the most demand. This demand increases the cost of getting a transaction added to the chain (gas) and results in congested, slow blockchains.

Zero-Knowledge Proofs - This concept isn’t really specific to scaling solutions, but it’s an important definition to clarify before talking about some of the scaling solutions. A zero-knowledge proof is a cryptographic method for proving that something is valid without needing to expose the specifics of the information.

For example, let’s imagine I am a buyer on Craigslist, looking for a television to purchase from some random person on the internet. Someone messages me to say they’ve got the TV I’m looking for - but the profile is anonymous.

As the buyer, I want to make sure that the seller actually has the TV before meeting up with them. But the seller might not want to share their personal information (drivers license, home address, pictures of the inside of their home) to random people on the internet, and on top of that, the seller wants to know that I’m a real person too! Neither one of us wants to share our personal information.

Using zero-knowledge proofs, I could prove to the seller that I’m a real, verified person without telling them who I am. On the other hand, the seller might prove that they actually own the specific television and that they are a legitimate seller, again, without exposing any of their sensitive personal information.

These are complex cryptographic primitives, so this really is an oversimplification here. Mostly, these zero-knowledge proofs can be used to solve security, scalability, and privacy challenges in the world of crypto.

Layer 2 scaling solutions - People really want to do stuff on Ethereum. It’s the most decentralized and established smart contract computing platform in the world, Ethereum has attracted the widest network of developers building blockchain-based applications. As a result of this activity, the demand to get transactions included on the Ethereum blockchain causes gas prices to get pretty high sometimes, which means Ethereum can be slow and expensive to use.

The blockchain trilemma implies that any blockchain that has optimized for security and decentralization will be making a trade-off in scalability. Since decentralization and security are so important to the promise of what blockchains can achieve, scalability has become the hardest one to figure out. Ethereum is betting on a wave of changes to help solve the scalability issue.

One of these changes is a shift from users interacting primarily with the Ethereum blockchain itself (known as “Layer 1”) to instead interacting with Layer 2 scaling solutions. Basically, this means moving most transactions and applications on Ethereum’s mainnet to Layer 2, which are blockchains that use Ethereum’s security and decentralization, but can scale transaction volume several orders of magnitude above what Ethereum itself can do. Layer 1 Ethereum will be responsible for consensus specifically, while the Layer 2s will be actually executing the transactions and code.

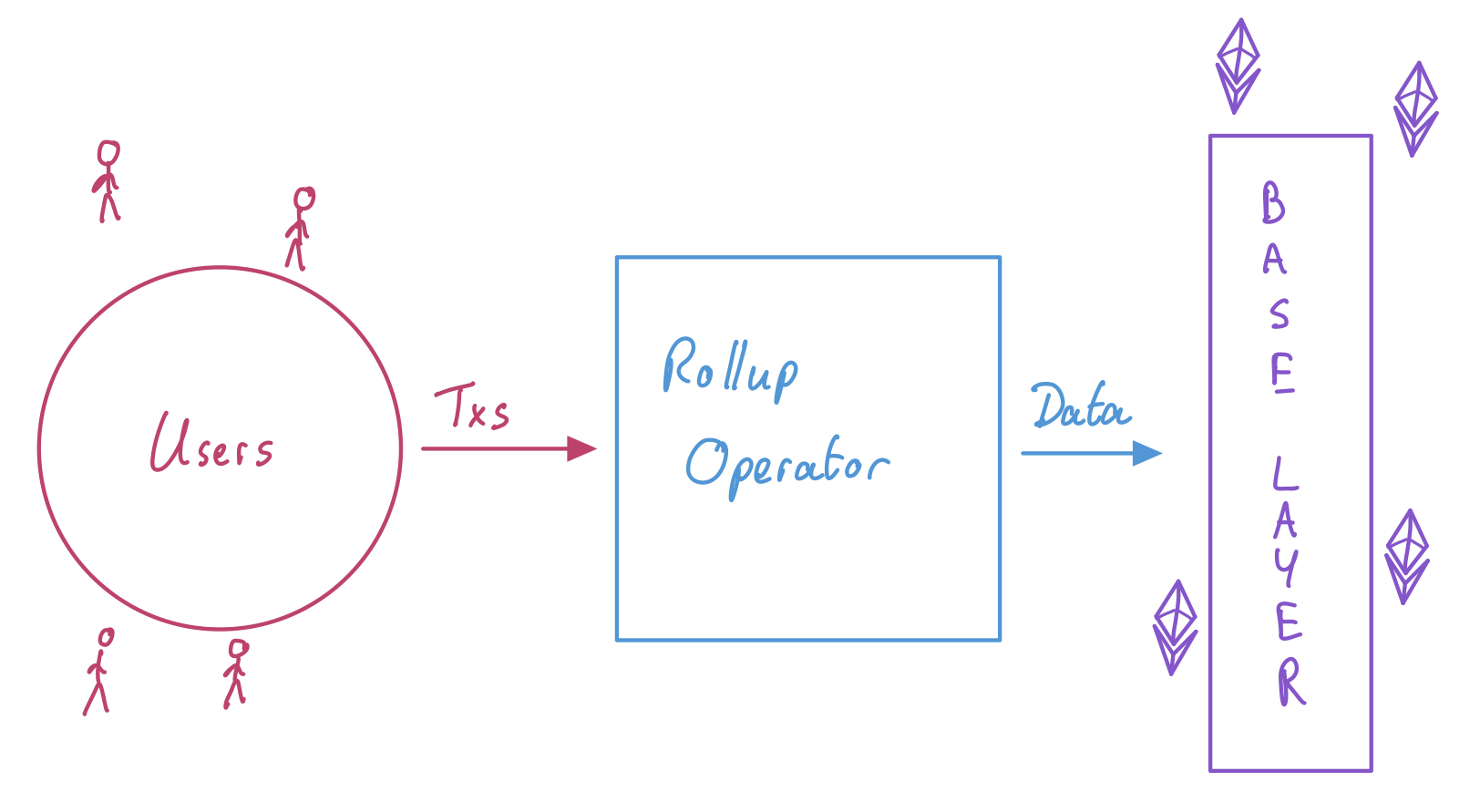

Rollups - Rollups process a bunch of transactions on their own separate blockchain. After executing these transactions on their own chain, the rollup compresses all of these transactions into smaller packets of information. These smaller packets of information get ‘posted’ on Layer 1 Ethereum, which means that the rollups inherit the security of the Layer 1 chain while scaling the number of transactions that can be processed (since the information is compressed).

These much smaller packets of transaction information include proof that these transactions were processed in a way that would abide by the rules of Ethereum.

Image from: Understanding Rollup Economics

This might sound like a compromise of decentralization. But a key aspect to rollups is that Ethereum can just check the proof rather than doing the work of ‘proving’ all of the individual transactions, which saves an exponential amount of effort (so it makes Ethereum more scalable!). Because Ethereum gets the final say on whether these rollup transactions are allowed to be posted onto Ethereum, all of the rollup transactions are still fully secured by Ethereum without compromising on centralization.

There are a couple types of rollups. The difference between rollups is the method that they use to prove to Ethereum that their transactions are valid.

Optimistic Rollups - These types of rollups keep records of the proofs of the transactions on the rollup, but only present these proofs to Ethereum when Ethereum requests the proof specifically. Instead of having to prove to Ethereum’s mainnet that every transaction is valid, optimistic rollups provide proofs when necessary, which helps in terms of scalability.

ZK Rollups - These types of rollups use zero-knowledge cryptography to prove that transactions are valid without having to show all of the details within the transactions. Zero-knowledge proofs are explained above, but the main point is that these rollups save a lot of space by only needing to show the smaller zero-knowledge proof instead of the entire transaction.

Sharding - Sharding is the process of splitting up a blockchain into smaller shards to reduce congestion. Sharding makes Ethereum more accessible - basically, nodes will only need to hold the data about the specific shard they’re connected to, rather than the entire Ethereum blockchain - while also making Ethereum more scalable.

Sharding is one of the planned improvements to the Ethereum blockchain that will be important after The Merge.

Beacon Chain - The Beacon Chain is the foundation for Ethereum’s transition away from Proof-of-Work and into Proof-of-Stake consensus. The Beacon Chain exists separate from Ethereum’s blockchain today, and the Beacon Chain introduces staking, which is necessary for the transition to Proof-of-Stake.

Soon, the Beacon Chain will be merged with the existing Ethereum blockchain, introducing PoS officially as the Ethereum blockchain’s consensus mechanism and signaling a major turning point for the future of Ethereum.

The Merge - It is fitting to end this guide with a term like The Merge. In the next few months, Ethereum Mainnet and the Beacon Chain will merge in the most widely-anticipated event in the blockchain world…. Ever.

The end of the Proof-of-Work era for Ethereum is only a few months away, and the repercussions of this switch could potentially be massive. If for some reason, The Merge fails, the impact will reverberate across the entire crypto landscape. But if successful, The Merge could be a signal that Ethereum’s journey to becoming the global settlement layer is closer than expected.

Resources

So that’s it! That’s a Simpler Guide to Ethereum.

First, we worked through the foundational pieces of what a blockchain is and why blockchains are important before diving deeper into some of the specific features of the Ethereum blockchain.

Then, we talked about some of the killer applications being built on top of the Ethereum blockchain; wallets, DeFi, DAOs, and NFTs.

After that, we wrapped up with the future of Ethereum, discussing the shift to Proof-of-Stake consensus and describing how Ethereum hopes to solve the blockchain trilemma.

All of these definitions are simplified versions of complex topics, but hopefully this guide inspires you to dig deeper into the world of Ethereum. Below, I compiled some resources for those of you looking for the next steps in your learning experience. If you want to reach me for questions or feedback, DM me on Twitter.

Thank you to Josh Stark, Bethany Crystal, Daniel Schlabach, Nico Kuzak, Adam Tzur, Naz Rizvic, and Miguel Lemos for your thoughtful help and feedback here!

Good places to go next:

The following resources were compiled by the Ethereum community in this document after Josh Stark and I began the compilation in late 2021.

General resources

Ethereum.org - What is Ethereum? - learn the basics, with links to material covering advanced topics

ETHHub- community maintained resources covering wide variety of Ethereum topics

Ethereum Foundation Youtube Channel - ethereum talks & community developer calls

Devcon archive - archive of all videos & talks from the annual Devcon conference

Scott Sunarto’s Working in Web3 Handbook - guide covering various topics

Blockchain@Berkeley Courses - free online courses about cryptocurrency

Finematics - video explainers for various topics in ethereum, web3, defi

Fellowship of Ethereum Magicians - a forum for the crypto community to have a place where anyone can join, create topic and discuss mainly about EIPs and technical difficulties of the Ethereum ecosystem.

Ethereum Wiki - Ethereum wiki covering all things related to Ethereum

Blogs, Media, and Research

Tim Beiko’s AllCoreDevs Updates

Ben Edgington’s What’s New in Eth2 blog

Ethereum: The Infinite Garden (feature documentary film in production)

Podcasts

Books

Enjoyed this post?

Subscribe to be notified when I publish something new.